Artist Research

MA application:

MA Questionnaire

1. Please describe and analyse your creative practice. (max 1500 characters)

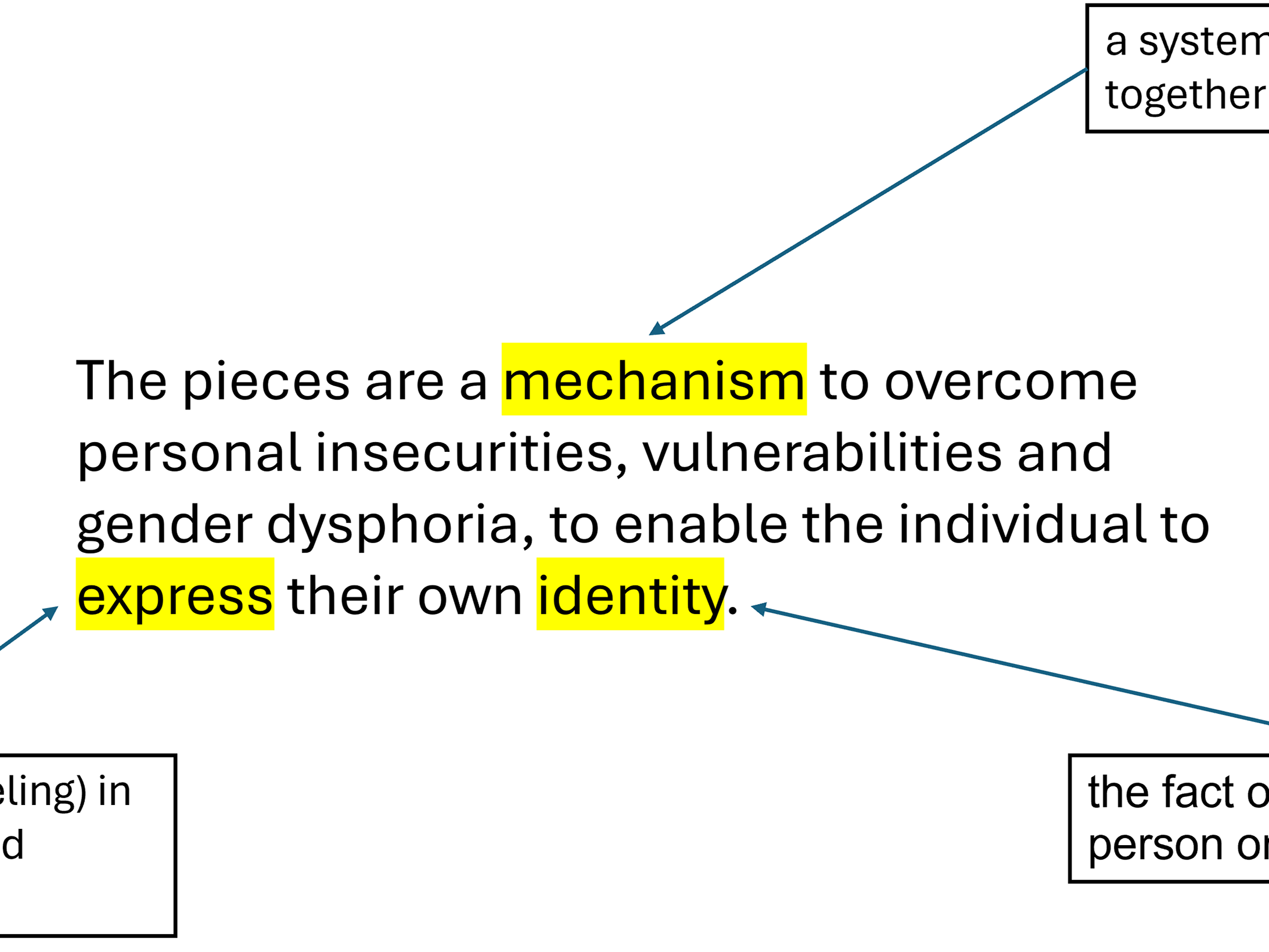

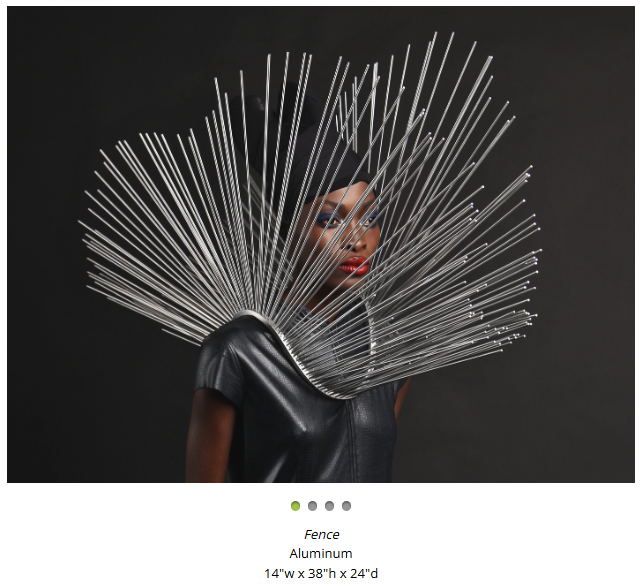

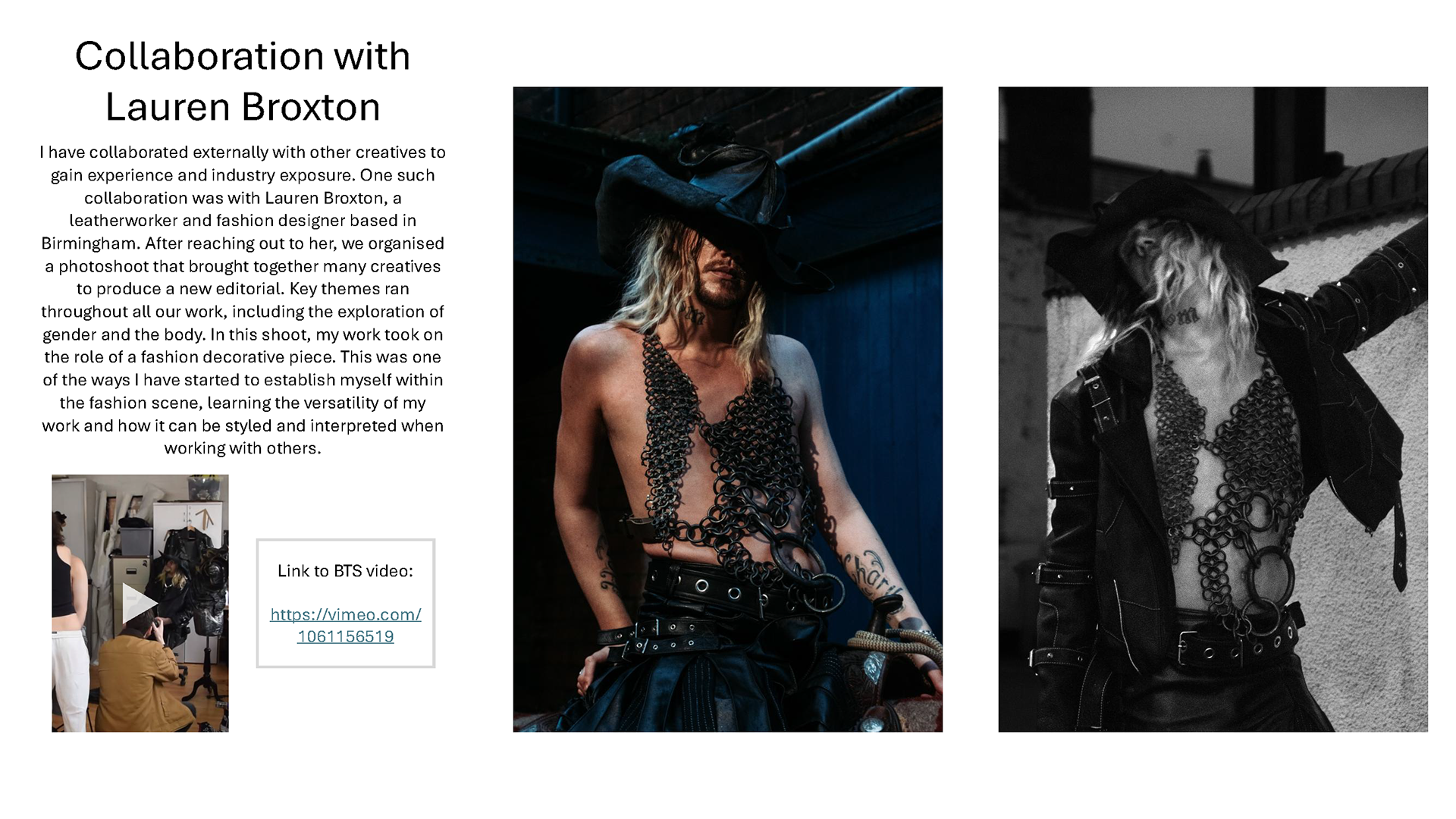

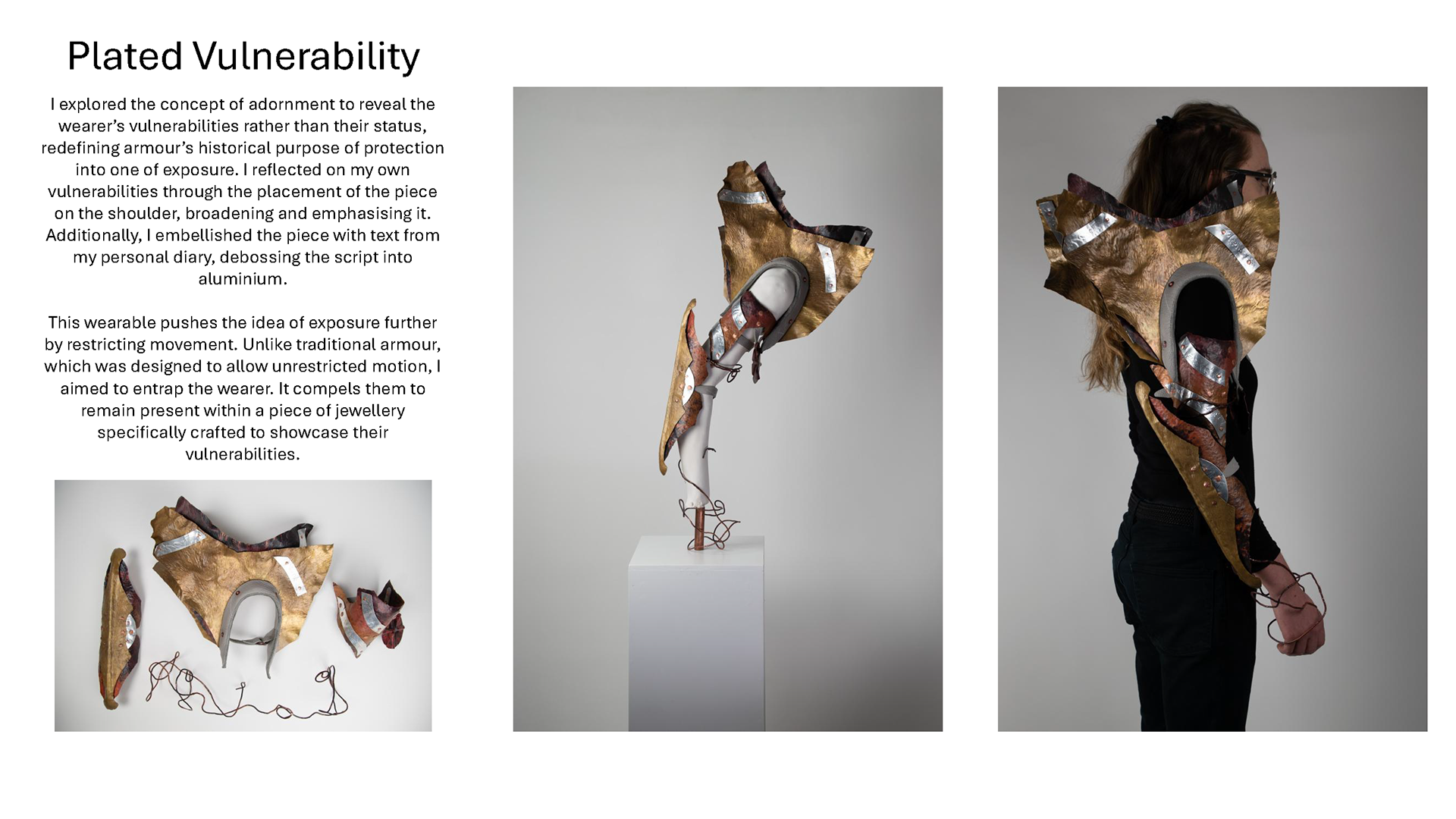

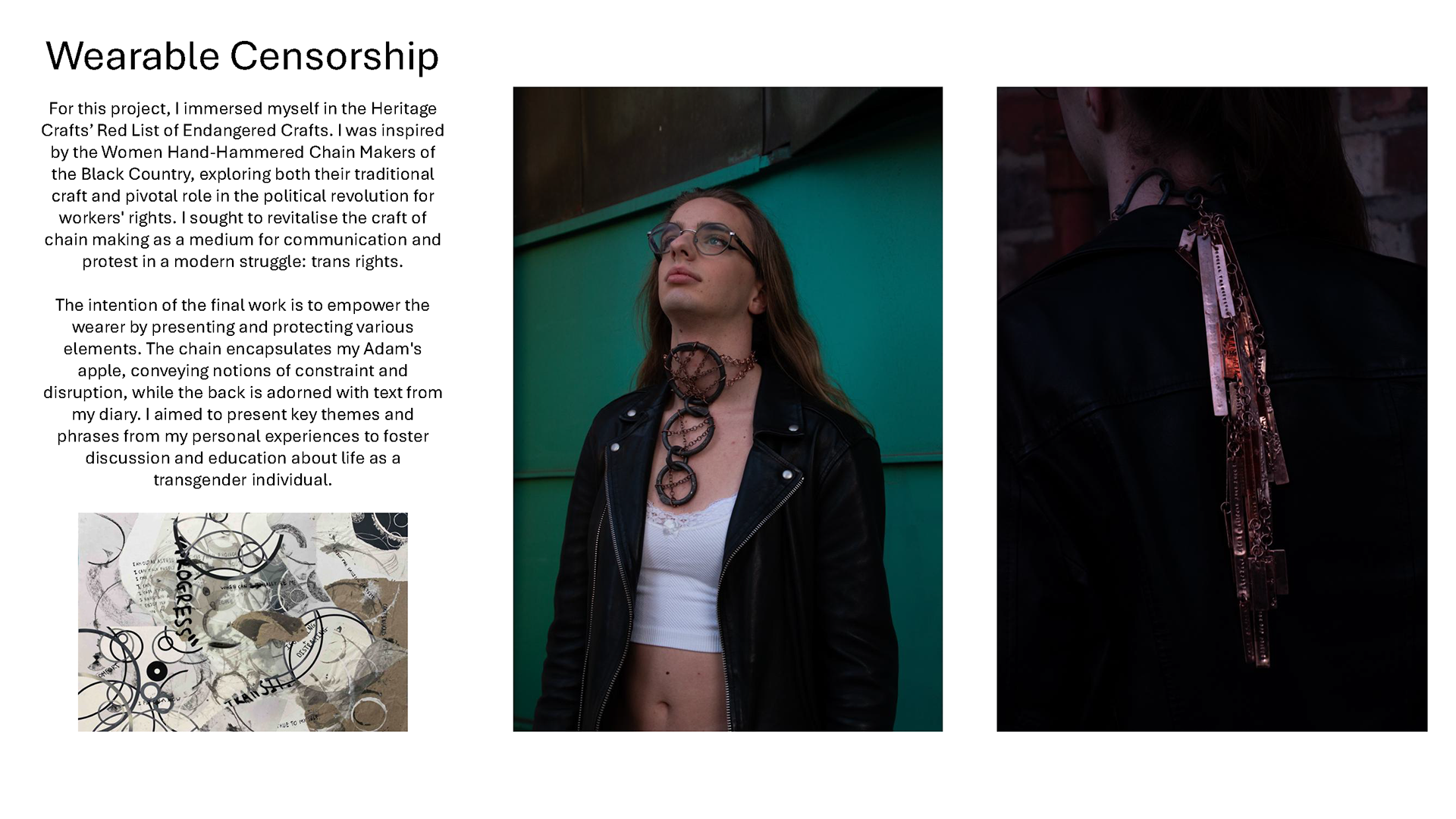

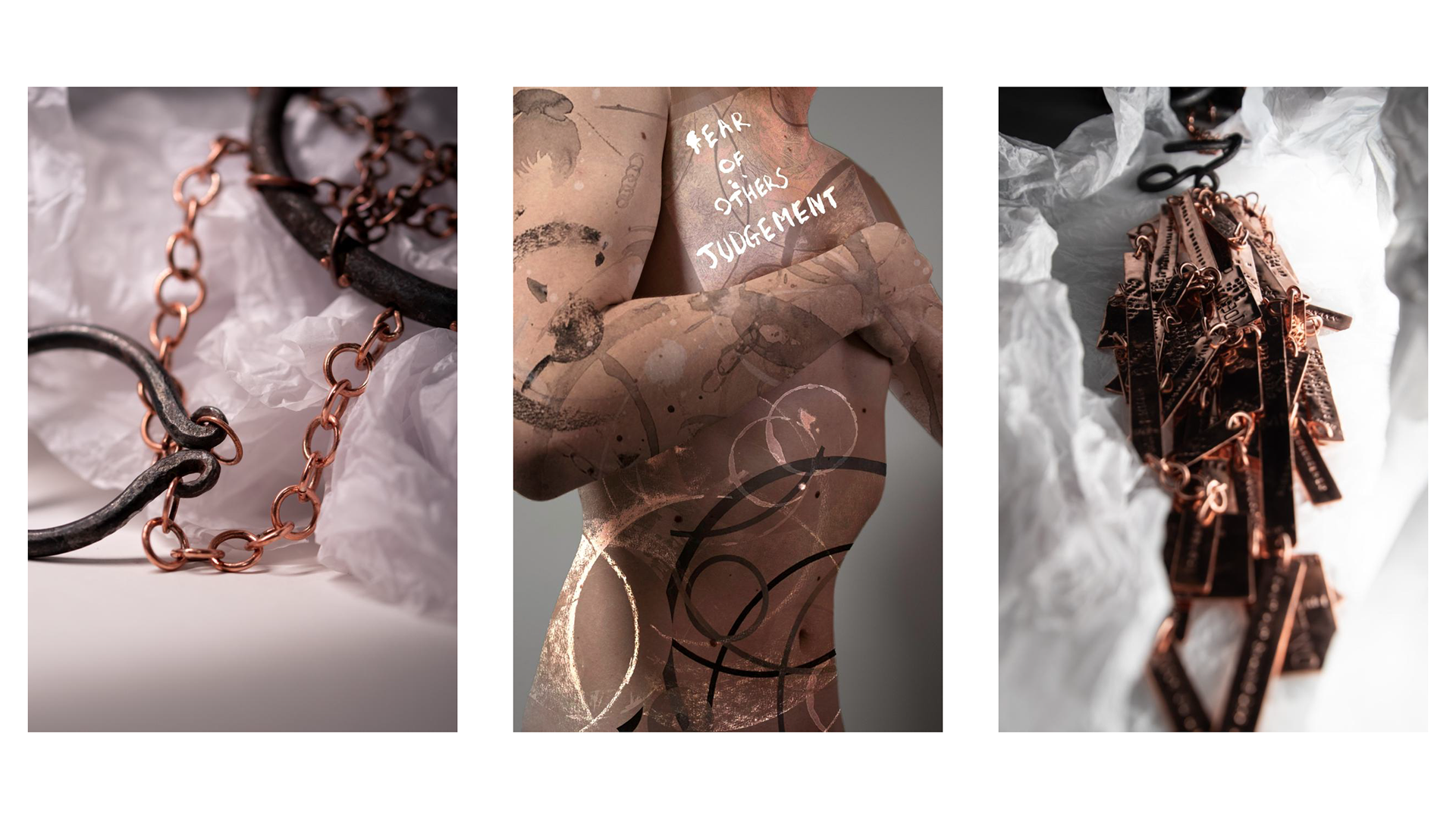

In my practice, I explore how jewellery can be worn as a protective layer. The piece can provide the wearer with a blanket of security, shielding them from the view of others. Additionally, this protective layer can instil confidence. Jewellery must have a reason to be placed on and designed around a specific location on the body. My practice involves utilizing the connotations related to areas of the body to guide the narrative of the piece. I explore the transfeminine body, choosing a location of insecurity in which I wish to not only protect but also empower. I believe reflecting on my own relationship with the body enables me to investigate the nuances and specifics, rather than taking a wider sweeping view of the body. Despite these being based on personal experiences or relationships, they often transcend to many individuals with the same shared experiences in the transgender community.

In my recent work, I have started to connect and collaborate with other members of my local transgender community. This body of work aims to tackle their personal relationship with gender dysphoria and showcase the breadth of individual experiences that construct a community.

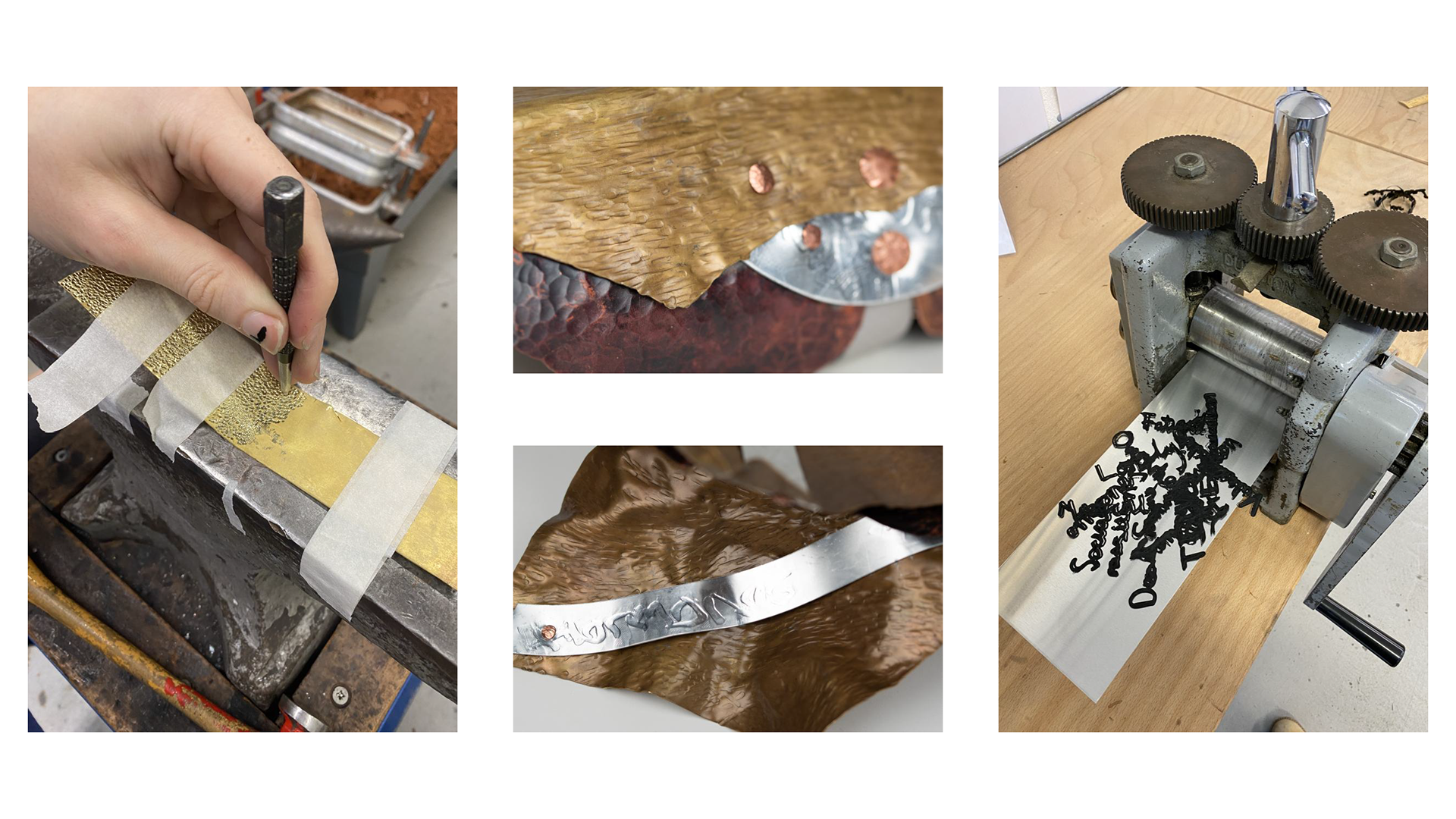

Core to my practice is staying true to materials. I work predominantly in steel, copper, and brass to create my body sculptures. I feel that the weight, texture, and temperature play an important role in the presentation of protection.

2. Analyze and reflect on a specific topic that interests you based on one example (a design object, a work of art or literature, a visited exhibition, personal or cultural experience/event, etc). (max 1500 characters)

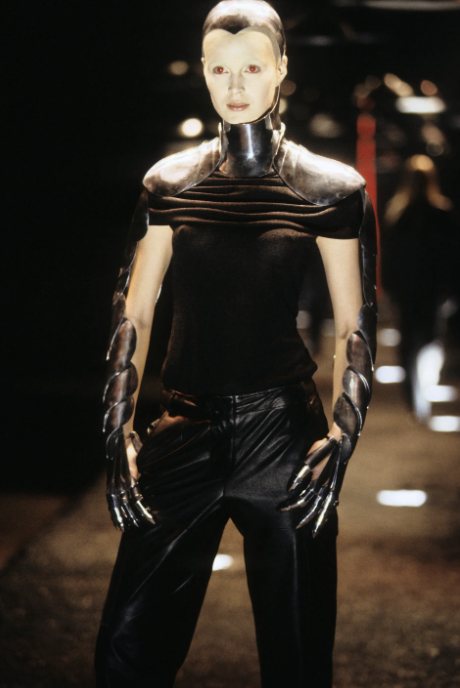

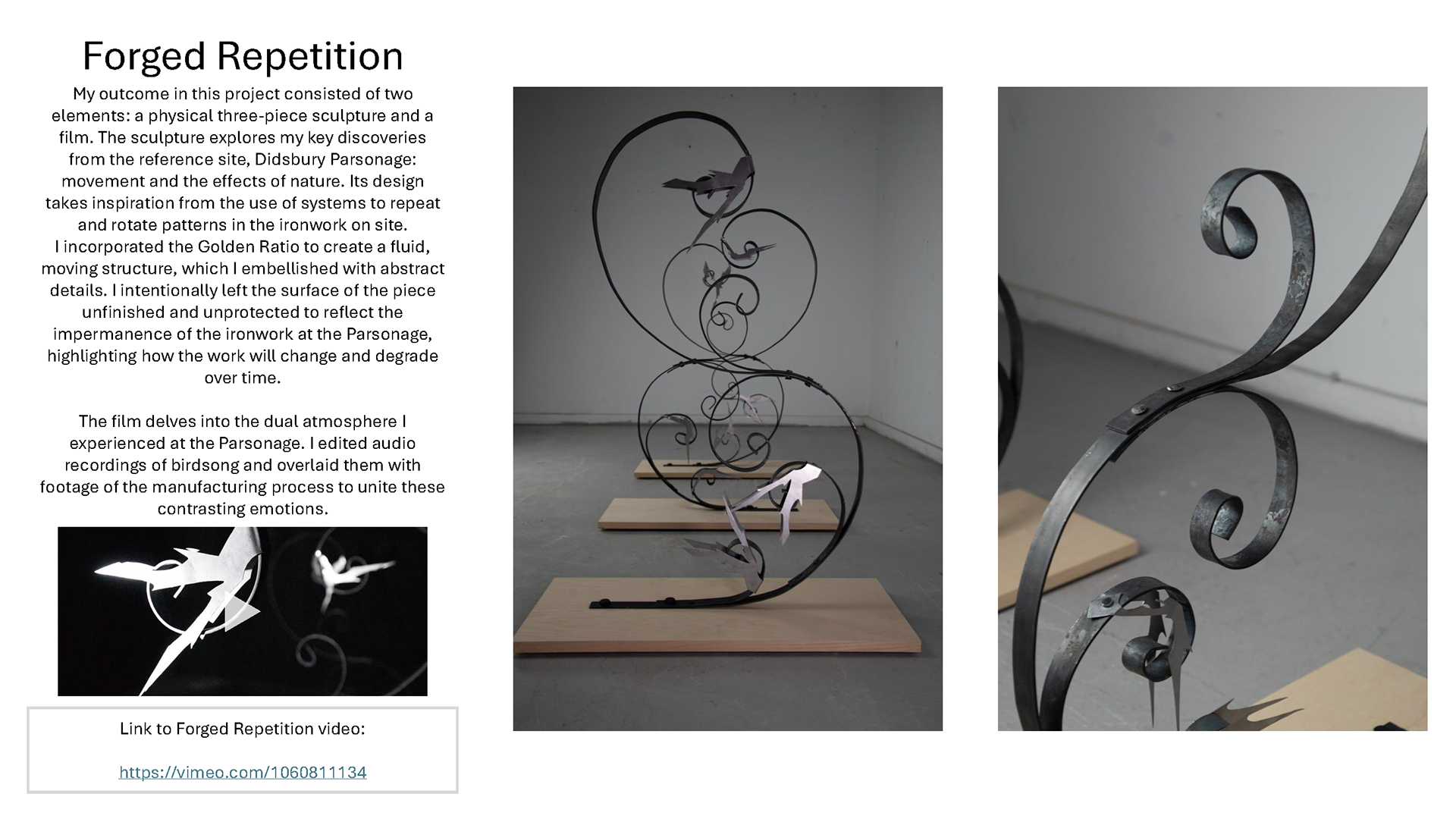

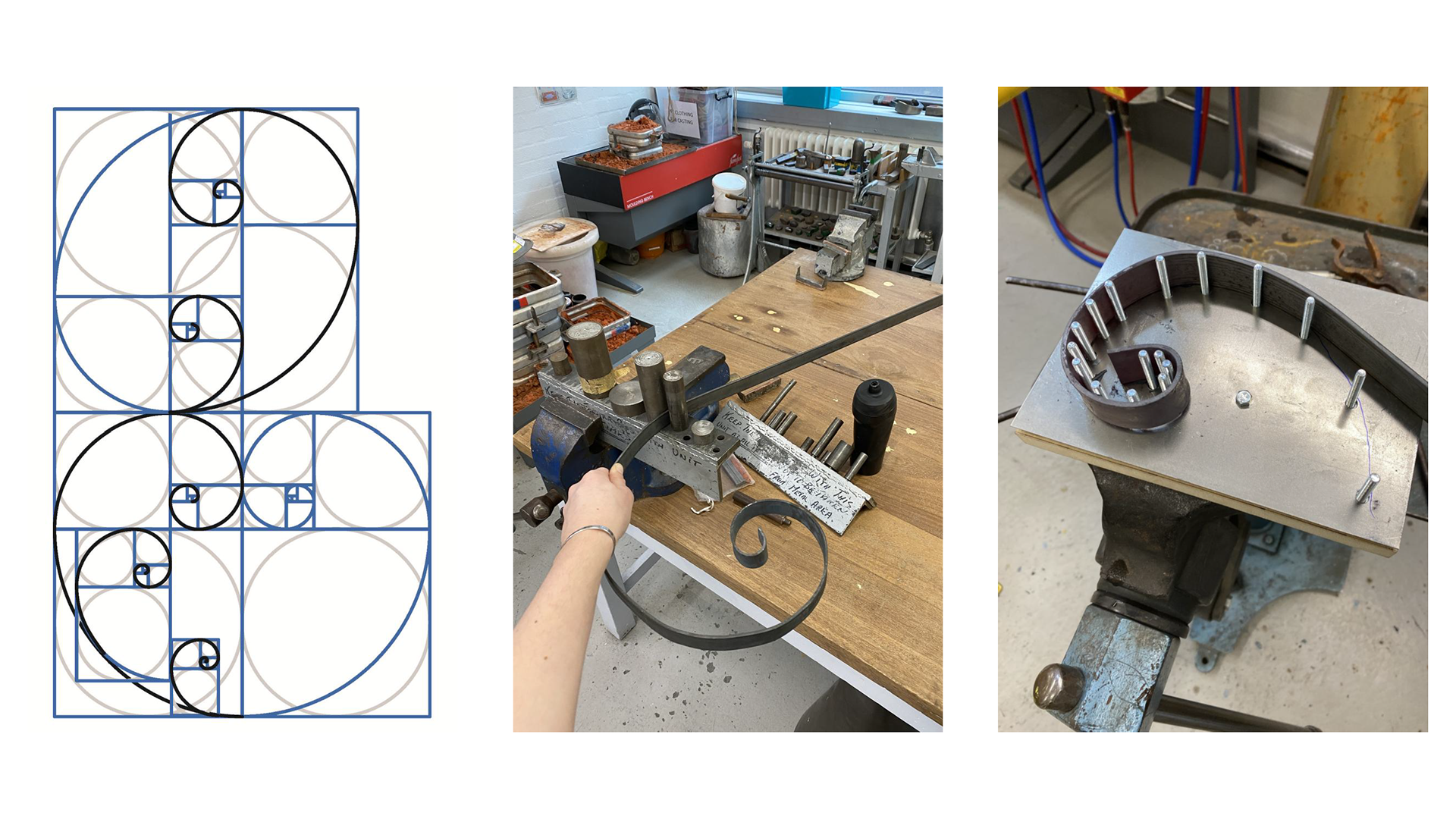

A major turning point in my practice was visiting the Royal Armouries in Leeds during my second year and the subsequential armoury trips. This has informed both the forms of my body sculpture and helped to guide the narratives of my work, centring around how we protect the body.

Considering the historical protective purpose of armour, it served to defend the wearer against physical harm. It did this by covering the body and shielding it with sheets of steel and iron shaped to redirect incoming blows away from the individual (Woosnam-Savage, 2017). Drawing inspiration from this, the covering and redirecting are two key elements worth focusing on. I hope to extract and develop these ideas into new armour or jewellery. In the same way that armour historically spread the physical blow throughout the plate armour or deflected it from a particular location, I seek to shift the viewer’s attention elsewhere.

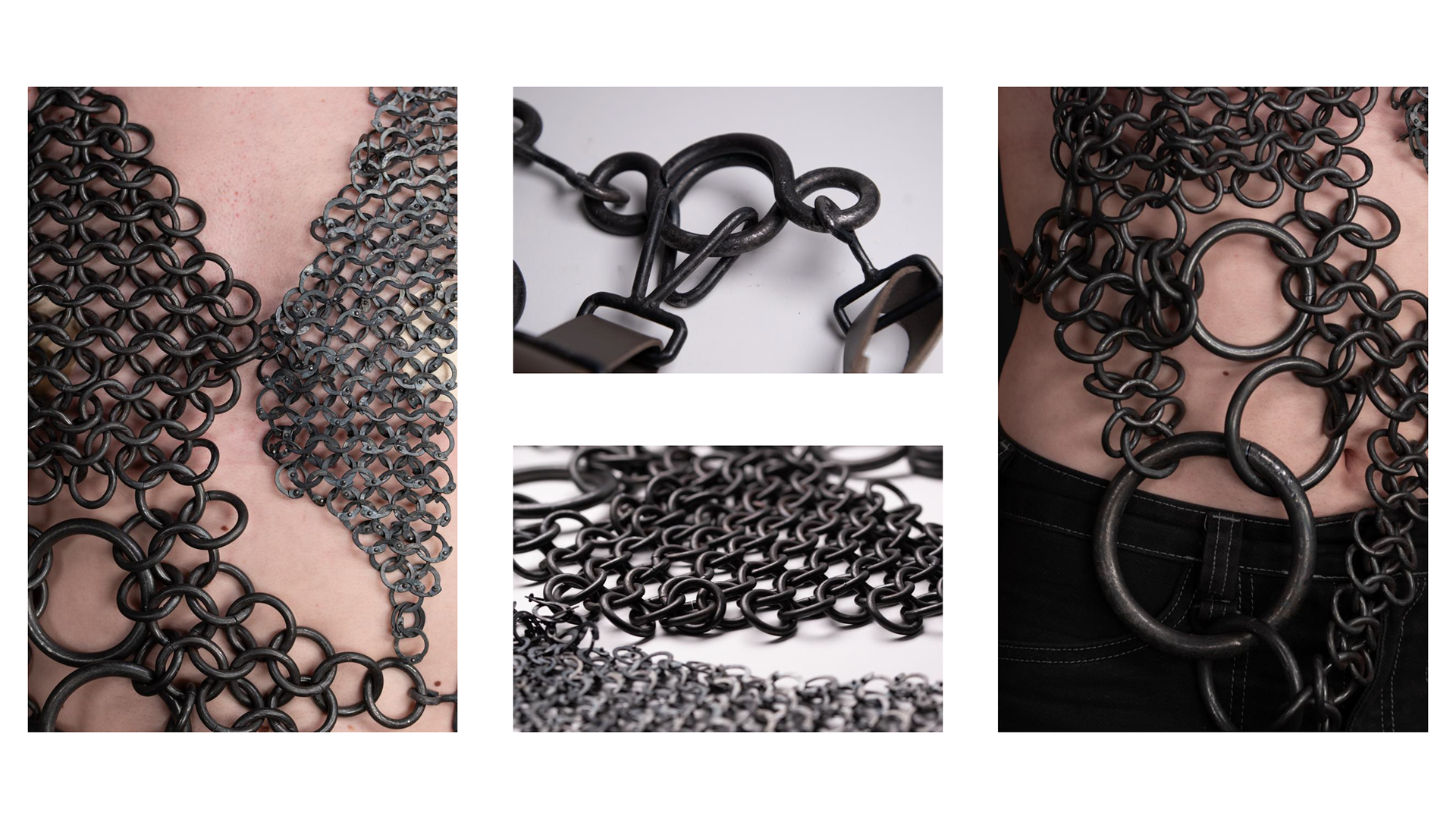

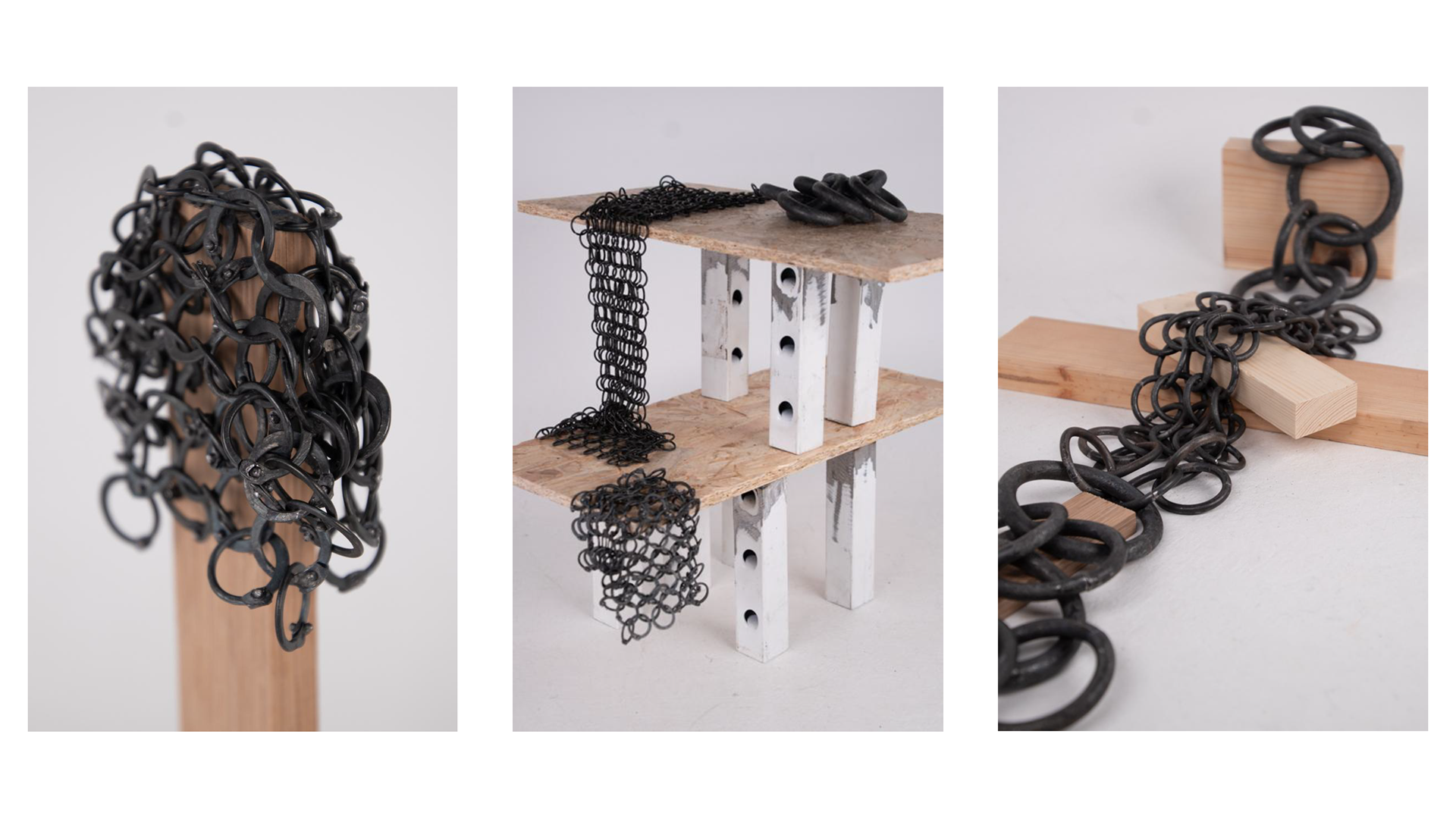

A key difference between plate armour and mail is its permeability. Rather than being one continuous plane, there are small regular pockets of negative space, which can be penetrated. Looking back at the historical impact of this, thrusting and piercing attacks were the downfall of mail and resulted in the technical development of plate armour (Woosnam-Savage, 2017). My current body of work seeks to reimagine these downfalls and explore the exposure of the body, and how we can cover or hide vulnerabilities using jewellery.

3. What does ‘craft’ mean for you as a noun or verb? Please describe your previous experience in the field of design and crafts. What do you think is essential to communicate through making? (max 1500 characters)

Craft exists as an umbrella term that encompasses the different traditional skills and materials used to produce objects. However, as technology advances and the access to information grows easier, the boundaries of these disciplines are blurring. I believe that in the future, the labels that have historically divided the industry will become less apparent. Therefore, Craft will become interdisciplinary, and each craftsperson identity won’t be tied to traditional trades.

For me, the action of crafting is as important as the outcome. My work serves a dual purpose: to generate conversations and awareness around queer issues, and the making process is a way of coping with everyday struggles. Frank (2022) introduces the idea that the physical action of forging can help individuals who are struggling with gender dysphoria to expel emotions into the material. The action of making also helps individuals gain control, as steel can be manipulated into any form the craftsperson desires. This contrasts with other elements of their life where change and control are restricted. I extend this into my work, where I use steel to alter and manipulate the body.

Frank (2022) describes the process of forging and metalworking as a grounding experience, one which can bring the craftsperson into the singular moment and give them focus. The benefits and results of crafting are therefore ever-changing and fluid, as our thoughts during the making and the desired results shift through our experiences.

4. What questions and thematic do you currently see yourself dealing with as part of your thesis research?

During my current project I am exploring the different vulnerabilities and experiences of gender dysphoria in the transfeminine community. I have been working alongside other members of the community, interviewing them to discover their person experience to produce a physical body sculpture to address these challenges.

I wish to analyse the materiality and immateriality of my work, and question why these physical outcomes are necessary to generate discussion around the struggles of queer individuals and communities. I want to study the impact of physical work to generate these conversations or if producing jewellery shuts down and limits this. Could a performance of a workshop have the same impact as physical work? I wish to explore alternative ways to open the discussion that can address and bring light to the specific individual stories that construct a larger community.

5. Who or What inspires you? Explain!

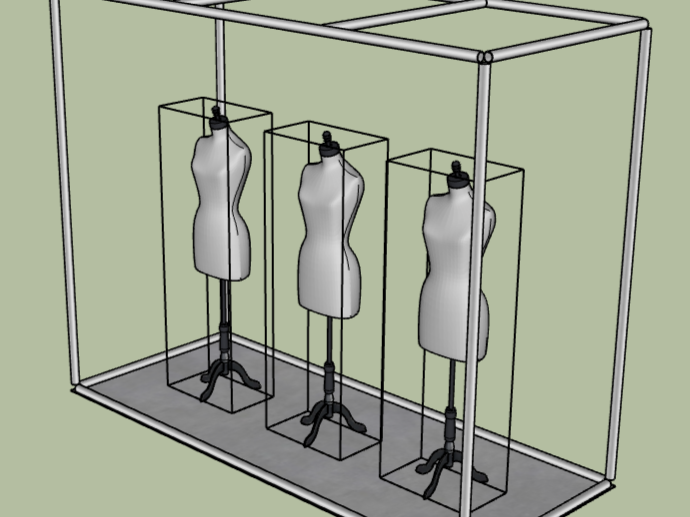

A key inspiration in my current exploration for the contemporary use of chain mail is Studio Katherine James. She explores chain mail both as a material, whilst questioning its historical connotations. Her work ‘Lace Armour’ is a screen made from galvanised steel wire mail, in a symmetrical pattern and suspended from a frame. The frame is made from scaffolding poles and places the top and vertical sides under tension, with the weight of the structure pulling it downwards. Additionally, the scaffolding frame creates a bold and harsh border for the chainmail piece, visually transforming the traditionally harsh and heavy nature of chainmail into draping tapestry. The vertical symmetrical lines create harmony and uniformity which reinforces this idea. The chainmail structure appears to be formed from one large uniform sheet which James has intentionally distorted and disrupted. The border of the chainmail is made using the traditional 4 in 1 European weave utilizing the same sized rings. She has then broken this apart and disrupted the flow of the pattern, introducing holes and breakages. The use of smaller rings and singular lines of chain creates finer details and provides control over the distortion.

Although this piece does not come into direct contact with the body, it still plays a critical role. The continued yet changing interaction between body, environment and object is evident in this work. As the viewer explores and moves around the piece each element is distorted. The chainmail structure breaks up and shrouds the view of the environment behind. James intended the screen to provide some disruption of the view but still allow glimpses through. The chain mail distorts the view, not fully blocking it, whilst the negative spaces give glimpses of clarity.

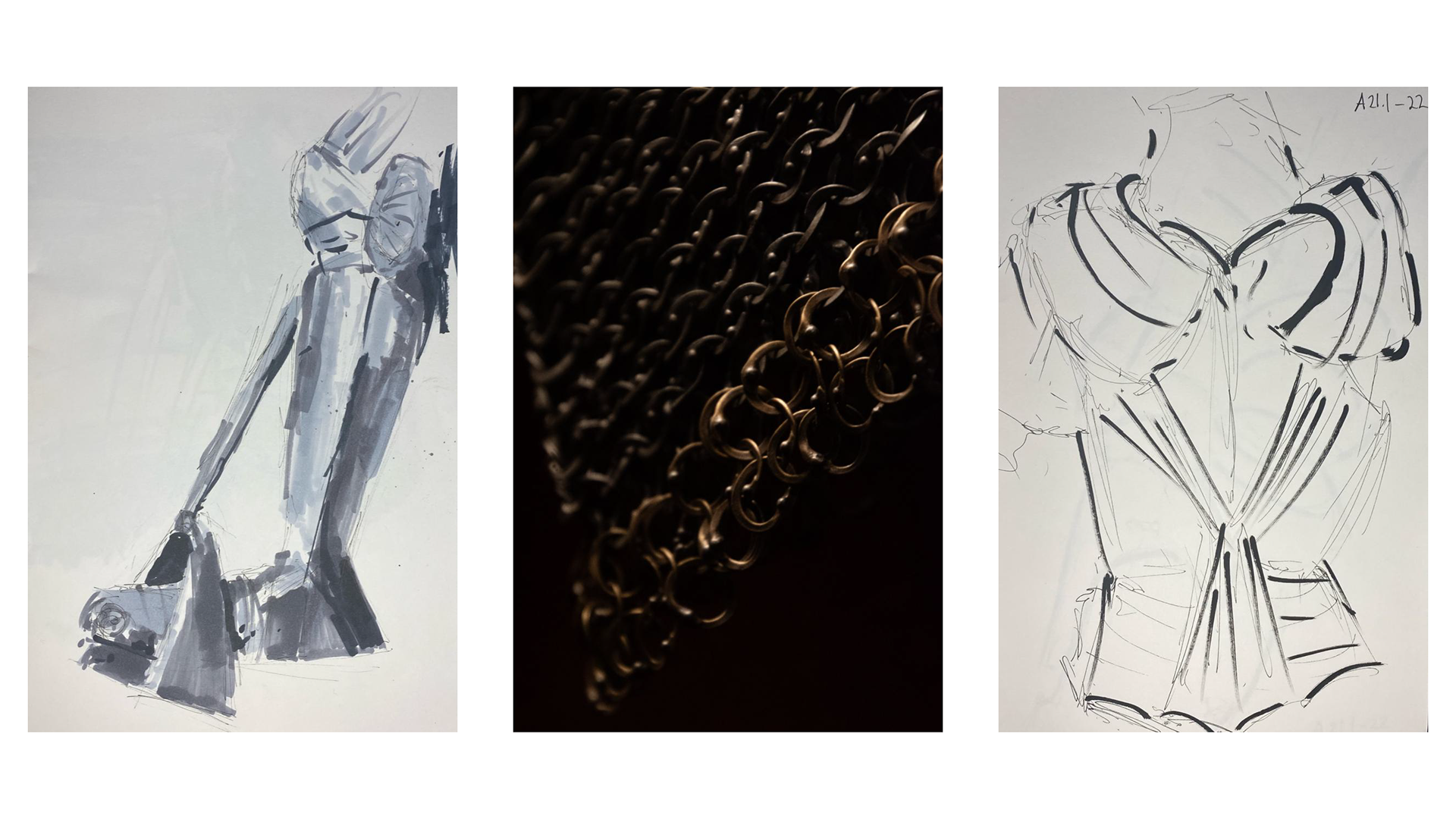

James’ piece ‘Lace Armour’ inspired me to explore disrupting and manipulating the traditional European 4 in 1 weave. I examine this throughout the project of ‘Armoured Femininity’ (see my portfolio). I was initially inspired to investigate scaling up the size of the individual rings. To enable fast and rapid prototyping I used a laser cutter to create a range of different sized links, changing both the wire thickness and altering the aspect ratios. I discovered that having a low aspect ratio such as 1:4 created a tight night structure, reducing the amount an object or light could penetrate through. Whereas using a higher aspect ratio such as 7 paired with a larger wire width, the structure was a lot loose and more open. I began to utilise the permeability of the structure to question how much the piece should shield and cover the body. I was inspired by the way James used the open sections in her work to draw the eyes and attention of the viewer into specific locations. I utilised the smaller links to provide full coverage and thus protection in areas that I wished to conceal, whereas I used the larger links to expose. My work has started to transform the importance of permeability from its’ historical physical properties of protection towards the blockading of a viewer gaze.

‘Lace Armour’ also encouraged me to focus on the drape and flexibility of chainmail. James uses a combination of a rigid structure and gravity to compose her work. Through my practical exploration I found that the effects of gravity played a crucial role in the production of mail. Initially I was designing and producing mail on the workbench, where the surface kept a consistent structure to the piece. However, when I lifted the piece up and placed it against the body the effects of gravity stretched and manipulated the structure. Through both the practical testing and studying James’ work I discovered that I needed to construct my mail directly onto the body. Similarly to the frame in ‘Lace Armour’ the body provides a supporting base which suspends the mail, whilst gravity attempts to pull the piece away and down. I discovered that the best way for me to create compositions that balanced these two elements was to work in an additive process, slowly expanding the structure. I produced the larger sections whilst it laid against the workbench and then brought the piece up against the body to ensure that it draped and fell into the intended form. I rotated between adding links directly to the structure and the body and then returning to the work bench to ensure a consistent weave. Designing the structure in laser cut greyboard first enable me to experiment quickly and alter the design by simply cutting out a section or link without the worry of loosing money or time if I had done so in steel. Once I had produced the pattern in greyboard I could reference it directly when making the final piece in steel. It laid out the exact number of links I needed and the order in which I needed to weave them together. Therefore, experimenting with the drape of my mail structures through rapid prototyping enabled me to balance the composition, placing the differing sized links for varying coverage.

6. Are there any specific skills, methods and forms of knowledge you are looking for in an MA programme? What are your expectations for the Craft Studies curriculum?

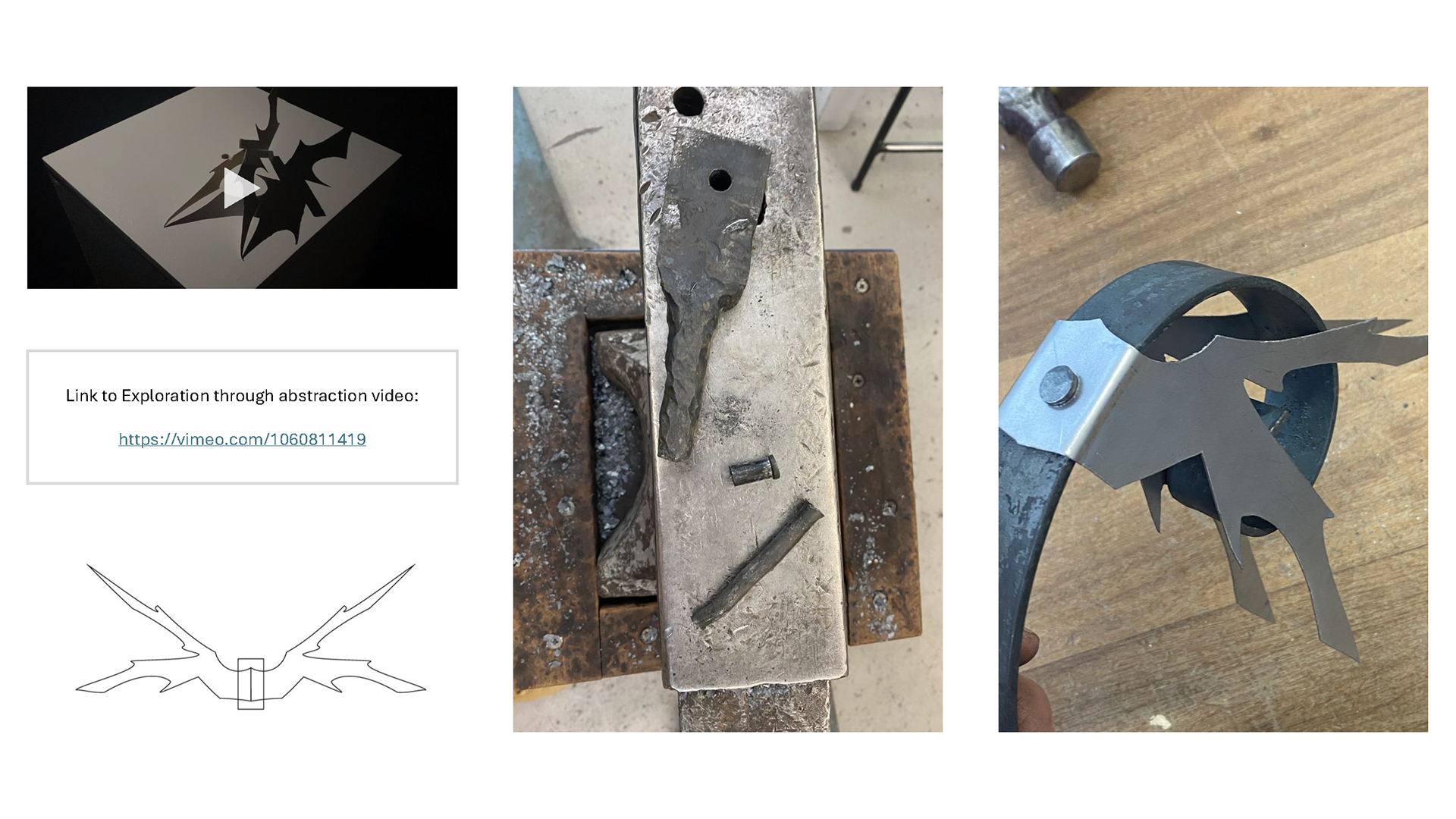

Blacksmithing

Research skills

Career crafting

Connections

International experience

Belonging to a community of artist that share similar concerns

7. What do you see yourself potentially bringing or contributing to the MA studies (e.g. skills, peer support, cultural diversity, independent initiatives, discussion topics, etc.)?

I have a committed and rigorous approach to my work and an inherent need to dissect and question my approach. My practice looks at combining traditional notions of craft which are often associated with mastery and control with emerging ideas of queerness which relates to fluidity diversity.

Another way I explore the relationships in community is through my experiences in team sports. I have played field hockey throughout my school and university career and found that this common interest brings together individuals from many walks of life. This social interaction exposed me to many different experiences and individuals who have helped to broaden my perspectives of others and communities.

8. Who would you see as your studio advisor during the first semester amongst faculty members? (find a list on the curriculum webpage)

Piret Hirv

9. Why did you choose the Estonian Academy of Arts? Where did you get your information about the programme?

My lecture at Manchester School of Art Patrícia Domingues recommended the course. As well as CJ O'Neill and Rudi Morris who have also work alongside Eka exploring 3D printed ceramics. These recommendations as well as visiting the facilities in person and talking to the lectures and technicians helped me gain an understanding of how the course operates.

10. How many different MA programmes are you applying to?

I have chosen only to apply to this course as I currently think that it is the only one that suits my current practice.